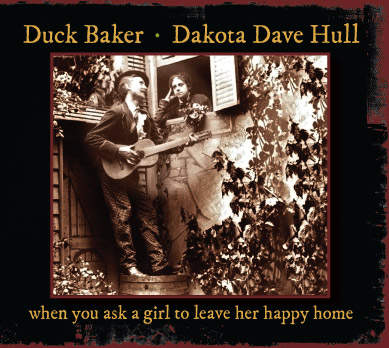

When You Ask a Girl to Leave Her Happy Home

When You Ask a Girl to Leave Her Happy Home

Dakota Dave Hull & Duck Baker

November, 2011 · Arabica Records CF-14

$15.00

Who’s Playing What:

- Ragtime Annie, Queen of the Earth, Child of the Stars, Johnny the Blacksmith medley & Hull’s Victory medley: Duck C, Dave E

- Dixie Darlin’ medley and Lonesome Moonlight Waltz: Duck B, Dave E

- Bull at the Wagon: Duck C, Dave D

- Jimmy in the Swamp medley: Duck F, Dave D

- Lady on the Green medley: Duck F, Dave E

- Silver Bells: Duck A, Dave B

- The Battle Cry of Freedom medley: Duck C

- Ducks on the Pond: Duck B

- Victory Rag: Dave F

- Erie Canal: Dave A.

Track List

- Bull at the Wagon

- Ragtime Annie

- Ducks on the Pond

- Hull’s Victory / Red Haired Boy

- Jimmy in the Swamp /Hannah at the Springhouse

- Lonesome Moonlight Waltz

- Victory Rag

- When You Ask a Girl to Leave Her Happy Home / Dixie Darling

- Battle Cry of Freedom / Cuckoo’s Nest

- Johnny the Blacksmith / Billy in the Low Ground / Hop High, Ladies

- Queen of the Earth, Child of the Sky

- Erie Canal

- Lady on the Green / Fiddler’s Dream

- Silver Bells

Credits:

- Produced by Dakota Dave Hull & Duck Baker

- Recorded by Dave Hull at Arabica Studio, Minneapolis

- Remix by Steve Wiese, Miles Hanson & Dave Hull at Creation Audio, Minneapolis

- Back Cover Photo by Gloria Goodwin Raheja

- Cover photo courtesy of Library of Congress

- Layout by Nick Lethert

- Thanks to Bernd Wannenwetsch and Cheryl Hall

Dakota Dave Hull and Duck Baker

Notes by Michael Crane:

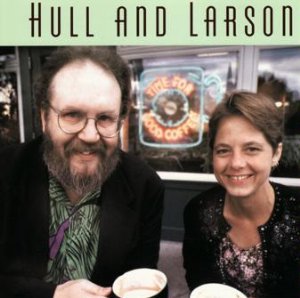

Duck Baker and Dave Hull met in 1977, when both were living in Minneapolis (Fargo-born Hull has been there most of his life; one year was enough for Virginia native Baker), but it was in the 1990’s that they got to know one another. At that time Dave was part of an excellent duo with mandolinist/guitarist Kari Larson, and Duck’s musical partner was the vocalist/multi-instrumentalist Molly Andrews. Between the two of them, Duck and Dave have worked in so many duos that their combining forces seems all but inevitable.

In addition to his partnership with Larson, Dave has also had significant associations with Sean Blackburn, Eric Peltoniemi, Peter Ostroushko and Cam Waters, while Duck’s guitar duo partners have run the gamut from bluesman Jerry Ricks to bluegrass icon Dan Crary to fingerpicking greats like Davy Graham and John Renbourn, to such modernists as Derek Bailey and Eugene Chadbourne. Given all this history, it should come as no surprise that the focus of this recording is very much on arranging. For the most part, Dave wields a plectrum while Duck plays fingerstyle. Since the latter typically involves a bass line and either melody or a harmony part, the possibilities for arranging are myriad, especially when applied to the array of instruments heard here.

Take Bull at the Wagon, for example. It starts with a flat-picked bass figure on the baritone guitar, then Duck comes in fingerpicking the melody over a standard alternating bass. On the C section, Dave doubles the melody in the lower octave, then takes over the melody on the second pass, with Duck fingerpicking harmony on the B and C sections. On the third pass, Dave puts the melody way down low. And so it continues; virtually every section of every tune gets a different treatment. Still, plenty of room is left for both solo and duo improvisation, especially on tunes like Ragtime Annie and Silver Bells. On the latter, Dave and Duck even manage to evoke the spirit of the great Six and Seven Eighths String Band of New Orleans, which seems fitting enough, given that Duck based his arrangement of the tune on a recording by trombonist Jim Robinson’s band.

In recent years, Dave has focused increasingly on his own considerable abilities as a fingerstylist, as he demonstrates on his two solo pieces here.

Since what’s good for the goose is, of course, good for other fowls, Duck proves, for the first time on record, that he knows which end of a pick to hold, handling the lead on Fiddler’s Green nicely.

I’ve been a big fan of both of these boys since it wasn’t even that much of a stretch to refer to them as “boys,” and have been looking forward to listening to this project ever since I heard it was on the way. It certainly exceeded my high expectations, and I can’t imagine it not delighting anyone who loves old-time music or top-notch guitar playing. But really, you don’t have to be any kind of specialist; so to put it more simply, I can’t imagine it not delighting anyone. -Michael Crane

Notes by Dakota Dave Hull:

A few years ago, Duck and I were invited to the home of our friend Dr. Bernd Wannenwetsch and were sitting around playing some of the guitars in his amazing vintage collection. Suddenly, Bernd asked, “why don’t you guys make an album together.” We thought it seemed like a good idea, if something of a challenge, given that we live about 4,000 miles away from each other! So we started swapping ideas about repertoire at long distance, and working up tunes every time we got together. The result, some three years later, is in your hand.

A few years ago, Duck and I were invited to the home of our friend Dr. Bernd Wannenwetsch and were sitting around playing some of the guitars in his amazing vintage collection. Suddenly, Bernd asked, “why don’t you guys make an album together.” We thought it seemed like a good idea, if something of a challenge, given that we live about 4,000 miles away from each other! So we started swapping ideas about repertoire at long distance, and working up tunes every time we got together. The result, some three years later, is in your hand.

Unlike that evening, we used instruments by modern luthiers in the making of this album. It really is a golden age for the acoustic guitar and we’re really lucky to have such fine instruments to play.

Dave’s baritone flattop (A) and his piccolo guitar (B) were both made by Charles Hoffman of Minneapolis. Charlie has been making guitars since 1970 and just keeps getting better and better. Bruce Sexauer of Petaluma, California made Duck’s Contemporary Nylon Stringed Guitar (C). It’s a wonderful guitar that departs slightly from the flamenco tradition. Don Young and the crew at National Resophonic of San Luis Obispo, California are responsible for Dave’s Style 1.5 baritone tricone (D), and it’s a winner. Finally, Dale Johnson of Fairbanks Guitars in South Windsor, Connecticut made Dave’s Jumbo (E), a structural copy of his 1935 Gibson Jumbo, and his L-00 (F). If you like what you hear on this record and need a guitar please give one of these fine folks a call. You won’t be sorry. -Dave Hull

Notes by Duck Baker:

Several of the tunes here are standards of the sort that every old-time musician picks up by osmosis, playing at sessions or in groups, or just by hearing thousands of times. Dave has no clear memory of where or when he started playing Billy in the Low Ground, Red Haired Boy, Hop High, Ladies or Ragtime Annie, while I’m pretty sure I learned Annie, Billy and Johnny the Blacksmith in the mid-70’s, when I was in a bluegrass band with fiddler Greg Roberts and banjoist Tom Coe. My own arrangement of Hop High, Ladies is based on the version Jerry Ricks got from Doc Watson. Jerry also taught me Dixie Darling, the Carter Family classic. But, while this great little tune has been played millions of time, the equally charming When You Ask a Girl To Leave Her Happy Home is far less well known. The 1927 version by De Costa Woltz’s Southern Broadcasters was the only prewar recording, and it has rarely been revived, which seems strange, as the lyrics are above average and Woltz’s band is among the most highly regarded early string bands.

Several of the tunes here are standards of the sort that every old-time musician picks up by osmosis, playing at sessions or in groups, or just by hearing thousands of times. Dave has no clear memory of where or when he started playing Billy in the Low Ground, Red Haired Boy, Hop High, Ladies or Ragtime Annie, while I’m pretty sure I learned Annie, Billy and Johnny the Blacksmith in the mid-70’s, when I was in a bluegrass band with fiddler Greg Roberts and banjoist Tom Coe. My own arrangement of Hop High, Ladies is based on the version Jerry Ricks got from Doc Watson. Jerry also taught me Dixie Darling, the Carter Family classic. But, while this great little tune has been played millions of time, the equally charming When You Ask a Girl To Leave Her Happy Home is far less well known. The 1927 version by De Costa Woltz’s Southern Broadcasters was the only prewar recording, and it has rarely been revived, which seems strange, as the lyrics are above average and Woltz’s band is among the most highly regarded early string bands.

Bull at the Wagon is usually played in A; Duck learned this G setting with another SF string band, the Beamish Boys, in which fiddler Hal Hughes liked to lean on the low open G string, the better to imitate a bull. Works fine on the git-fiddle, too!

This tune is clearly descended from an Irish “sand jig” called Kitty O’Shea’s, which Cal Scott has recently arranged for Kevin Burke to perform with a string quartet. The original tune is also known as Kitty O’Neill’s, and anyone interested should make a point of hearing Kevin’s elucidating introduction for it. (A sand jig was done on a music hall or minstrel show stage, where sand would have been sprinkled on the floor to enhance the sounds of dancers’ steps.)

Another tune of less-than-obvious Irish origin is Queen of the Earth, Child of the Sky, which turns out to be an incarnation of the slow air, The Blackbird. What’s curious about this is that there are so few instances of Irish slow airs being played by Appalachian fiddlers. In the old country, it was common for instrumentalists to convert the melodies of songs into instrumental pieces, exactly as it happened with The Blackbird, which then underwent a further transmogrification to become one of the most popular of all Irish set dances. One supposes this occurred after the song air crossed the ocean and found it’s way into the repertoires of some of the more remote fiddlers; this version comes from the legendary West Virginia fiddler Edden Hammons. I’m unaware of any instance of the dance tune in the OTM repertoire, however.

Erie Canal and Battle Cry of Freedom are the kinds of tunes so familiar in pop culture that they are rarely performed by revivalists, but we think they got to be well known for the good reason that they are great tunes. My setting of The Cuckoo’s Nest was learned from fiddler Frank Ferrel, but it’s widely known both as a dance tune and as a risque song, all over Britain, Ireland, and North America. I also thought it would be fun to work up duo flat-picking versions of two tunes Art Rosenbaum taught me long ago, Lady on the Green and Fiddler’s Dream. The latter was one of the first tunes ever recorded by its composer, Arthur Smith, on his 1937 session with the Delmore Brothers backing, while the former is from the repertoire of the great Nebraska fiddler, Uncle Bob Walters.

Dave used to perform Lonesome Moonlight Waltz with Kari Larson, but they never recorded their version. We wanted to have a waltz for this project, and this Bill Monroe classic is simply one of the best there is. We also thought it would be fun to arrange two wonderful tunes that celebrate donkeys, Jimmy in the Swamp and Hannah at the Springhouse. The former is found throughout the midwest and identified, again, with Bob Walters, but there’s strong evidence that it was in the repertoire of the legendary Ed Haley, who was from Eastern Kentucky but travelled extensively in neighboring states. Intriguingly Walters’ family was originally from the same general area. Hannah seems to be a West Virginia variant of the same melody, though it’s considerably more crooked and features a delightful modulation from A to C, just where Hannah makes her complaint. We learned it from the record of the same name by Melvin Wine, and took our version of Jimmy from another fine recording, by Illinois fiddler Mel Durham, called Skillet Fork.

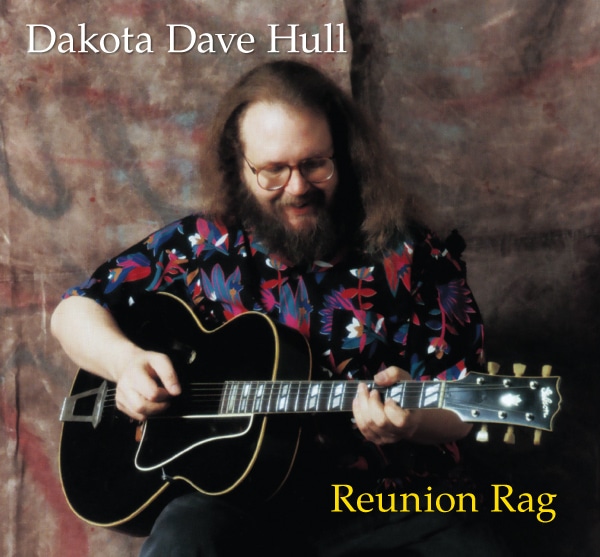

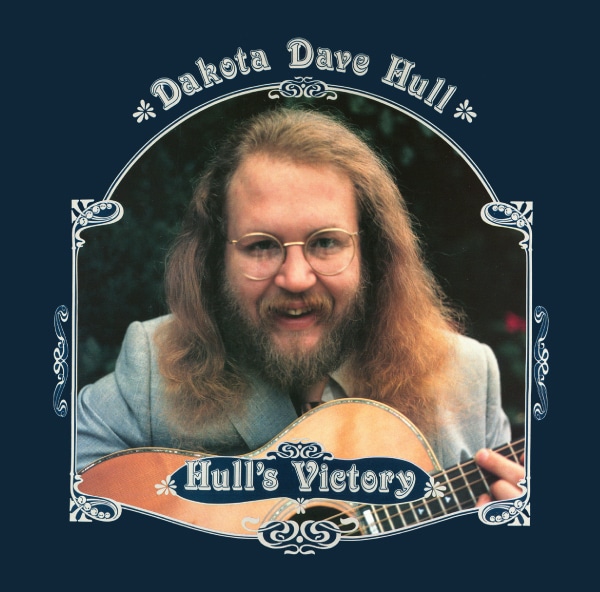

We also thought we’d include tunes that bear our names, so I arranged Ducks on the Pond, in a way that, I hope, underlines the mystery in this kind of old, modal tune, and Dave made a new arrangement of a number he recorded years ago, Hull’s Victory. He found the music for this one at the library of the Cecil Sharpe House in London, during a 1972 UK tour with Utah Philips. (I’m scared to ask whether this was a duo tour, or if Georgia Slim, Washington Phillips, Texas Gladden, Arizona Dranes, or Minnesota Fats went along.) This well-known contra dance tune celebrates a naval battle that occurred during the War of 1812, and over time both the dance and the tune travelled far from their New England home: It would shock my New England friends to hear an old Colorado Rancher ask me if I ever danced Hell’s Victory. From his description I was sure of the dance and told him it was Hull’s Victory, not Hell’s – Hull’s Victory with his famous ship, The Constitution. ‘No, no!’ he says, it’s Hell’s Victory! Called it that ever since I was a boy!’ (from Cowboy Dances, by Lloyd Shaw, 1943)

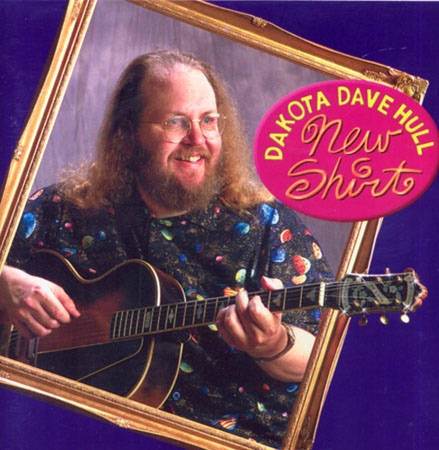

Victory Rag has long been popular with country fingerpickers, from Sam McGee to Doc Watson to Wayne Henderson. It is usually attributed to Maybelle Carter, though it sometimes gets confused with a piece of the same name by the great ragtime composer, James Scott. Apparently Maybelle performed it often on radio during the 1950’s, and taught it to members of the New Lost City Ramblers at a festival in 1963.

But Maybelle told the Ramblers she had learned it from another guitarist she knew from The Old Dominion Barn Dance radio program, during the 1950’s. We haven’t been able to get any further than that. Finally there’s Silver Bells. Bob Wills’ version of this is standard at this point, but it was written in 1910 by no less a pop-song composer than Percy Wenrich, and I was inspired to work it up before I had heard Wills play it, taking it off one of the first New Orleans jazz records I ever owned, back when the world was young. -Duck Baker – with thanks to Tony Russell, John Cohen, and Tracy Schwartz